(XIONG LEI) May 8, 2003

China Daily is an official publication of the Communist Party of China

When it was listed as one of China's first 180 key national cultural heritage sites in 1961, no expert on the State Council panel who drew up the list had ever actually visited the Guge ruins in western Tibet.

"They only happened to see some scenes of the ruins in a documentary film made by a crew sent from Beijing to Tibet in the 1950s," said Zhang Jianlin, a research professor with Xi'an Archaeology Institute in Northwest China's Shaanxi Province, who has worked on the ruins since the late 1970s.

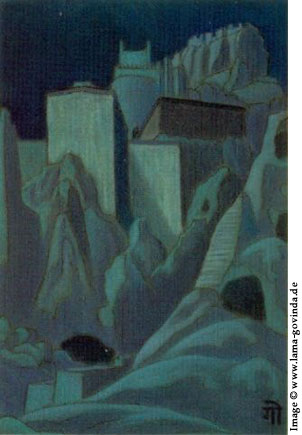

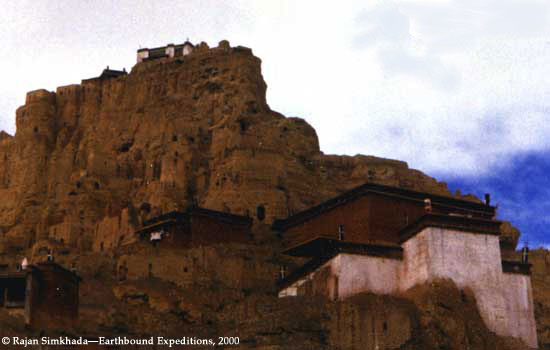

>From the grainy black and white shots of the ruined fortress, consisting of beehive-like caves and palace halls located on a hill 2,000 kilometres to the west of Lhasa and some of the murals, the experts decided that the site, though the least studied of several hundred candidates, was of vital significance.

Forty years on, it has proven to be a foresighted decision. The site of the long vanished kingdom, which has survived amid a sea of barren earth mounds in Ngari for more than seven centuries, has become an archaeological and art attraction for both Chinese and Western scholars. It also offers the promise of greater insights into the mysteries of ancient Tibet.

Chinese archaeologists all attribute the discovery of the Guge ruins to Giuseppe Tucci, an Italian Tibetologist who came across the site during an expedition in the early 1930s. Although he laid the foundations for archaeological work on the Guge Kingdom, Tucci's main focus was on the art of Guge frescoes, according to Zhang Jianlin.

Over the past two decades or more, Chinese archaeologists have conducted a far more systematic and all-round research on the site and the kingdom itself, resulting many interesting finds, Zhang said.

One such finding was a mask Zhang and his colleagues discovered among a pile of arrow shafts in a Buddhist cave in the mid-1980s.

A year later, after the mask was taken to Beijing for further examination, China's Catholic Association provided the answer. The writings, in Portuguese, were snippets from the Holy Bible.

"So the mask is not only an artifact of Buddhism, but also an evidence of local resentment against 'a heresy' among Guge subjects in the latter years of the kingdom," he said.

The mask is also testimony to the missionary endeavours of Christians in this landlocked area, which averages 4,000 metres above sea level, in the 17th century. According to reports by Portuguese missionaries to the Roman Catholic Church in Goa, India, at the time, the King of Guge had approved the building of a chapel in Tsaparang, capital of Guge, where Buddhism had prevailed.

The chapel was only half completed, however, when the Islamic Ladakh army besieged the Guge castle in 1632, wiping out the 700-year-old kingdom which had survived 28 lineal kings. The Guge ruins, covering 720,000 square metres atop a 300-metre hill, have since falling prey to the attacks of nature, their many mysteries still unsolved.

The foremost question, as yet unanswered, was how the Ladakh troops had come and why. As there is no written record of this period of history available, archaeologists and scholars can only conjecture on the basis of random artifacts unearthed to date.

"It was possible that the Buddhist monks in Guge wished to gain similar positions of power as held by their counterparts elsewhere in Tibet, positions of power which rivalled the royal authority," said Zhang Jianlin. "The unchecked increase of monks would inevitably compromise the kingdom's labour force and national defence capacity, as Buddhist monks were not engaged in production and would not serve in the army."

All this, said Zhang, was likely to arouse concern among the royal family of Guge and may have contributed to their decision to turn a new religion to counter the rising Buddhist power, when the Christian missionaries arrived in their remote corner of the world. The king's new found interest in Christianity, however, was possibly regarded as a threat to Buddhism, so ardent adherents to the religion may have sought the help of the

If this was the case, it backfired badly. The invading Ladakhs not only terminated the Christian mission, they also wiped out the entire kingdom.

While all this remains speculative and lacks supporting evidence, Huo Wei, who also heads the Tibetology Centre at Sichuan University, said what has puzzled archaeologists more is what actually happened to the Guge people.

"To this day we haven't found any descendants of the ancient Guge among present residents around Tsaparang," he said.

"It is unreasonable to assume that all the Guge people were gone when the kingdom was conquered. In fact 50 years after they occupied the kingdom the Ladakhs were driven away by the 5th Dalai Lama and his army, around 1682. So it is unthinkable that none of the Guge descendants were left."

An interesting point to note, said Huo, is the fact that Islam began to spread rapidly around the 10th century, almost coinciding with the rise of Guge. "The land of present Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region to the north of Guge and Ladakh in present day Kashmir to its west were Islamized, while Buddhism in India and Nepal to its south declined. Only Guge in western Tibet remained as a base of Buddhism for seven centuries, which indicates its strength."

Huo, therefore, proposed other reasons for Guge's fall than religious disputes, "say, for example, the deterioration of the ecology."

"I wonder if the population size had constituted too much a pressure on the arid land with limited water resources in Guge," Huo asked. Adding: " A deteriorated ecology would certainly weaken the kingdom's strength."

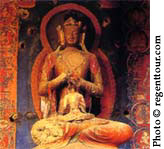

What fascinates Huo, Zhang and all visitors to the site are the remnants of the Buddhist civilization created by the Guge people. Of more than 300 houses and rows of about 300 cave dwellings in the Guge fortress at Tsaparang, only five halls are still in relatively good condition, where murals, clay sculptures and artifacts, demonstrating a well-developed culture, are found.

"Guge artists set standards for a type of art characterized by a clear and lyrical graphic form with vivid colouration unmatched anywhere," observes Khang Skabs-bzang Yeshe, a Tibetan professor of fine art at Sichuan University. "Rooted in the native culture of Bon, a shamanistic-style religion, the Guge art assimilated aspects from India, Nepal, Kashmir as well as other parts of China, and mirrors a remarkable diversity."

Huo Wei said that the Guge people were really admirable to create such brilliant masterpieces of Buddhist art under such harsh natural conditions.

"This raises the question of on what kind of material basis and in what ways the Guge people had exchanges with South Asia and the central parts of China," he said. "Buddhist monks alone could not support exchanges on such a scope, but we are not clear if there was a unique productive or trade system to facilitate them."

Some written records on the latter days of Guge remain, thanks to the reports by missionaries to the Church. "But we lack the documents and archaeological materials of the early and middle stages of the kingdom, especially the middle stages from the 12th to the 15th centuries," said Huo.

A dozen similarly devastated castles have been found in hills surrounding the Tsaparang fortress at some 20-40 kilometres distance. "We believe they are what we today call satellite towns of Guge," said Zong Tongchang, an archaeologist from the Palace Museum in Beijing, who has made several trips to Guge. "What isn't known again is how they were ruined."

Also unknown is how many fresco grottoes are hidden in those beehive-like caves around the sea of earth mounds.

"In the county of Zada where the Tsaparang fortress is located, 63 fresco grottoes have been discovered," said Huo Wei who has visited the site nine times since 1990. "We cannot tell how many more there are that remain to be unearthed."

A more intriguing question for Huo and his colleagues is the link between Guge and Shang Tung, a civilization that flourished in western Tibet until 1,300 years ago, according to Tibetan records. "But we haven't found any hard archaeological evidence of the legendary kingdom in ancient Tibet, which is believed to be a source of Tibetan culture," said Huo.

"What is certain is that the findings at Guge, so far, are only the tip of an iceberg," Huo said. Having been studying the lost kingdom for 10 years, he said: "I found that the questions constantly raised about Guge have far outnumbered the ones we can answer. The efforts of several generations are required to study Guge."